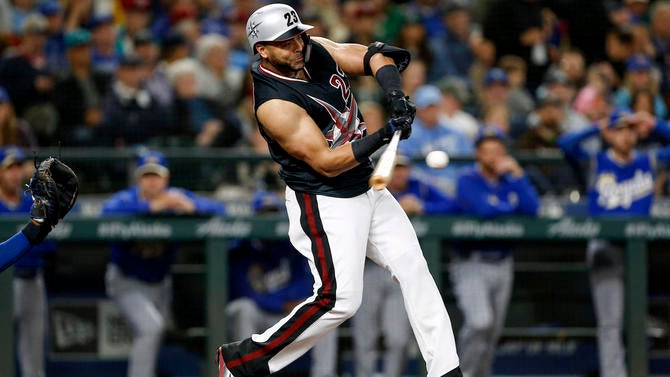

On Thursday, the Twins signed Nelson Cruz to a one-year, $14.3 million contract. If that sounds crazy, it should. Over the past five seasons, Cruz has smashed more home runs than any other player in baseball.

So how did he end up settling for a one-year deal for modest dollars? The answer is simple. Major League Baseball teams, once desperate to splash mountains of cash on power hitters, now turn their noses up at them. Considering their rock-bottom value in both trades and contract negotiations, we are now experiencing something once thought impossible: The death of the power hitter.

Thanks to the fine work of CBS Sports director of research John Fisher and his team, we can start to understand why teams are increasingly snubbing sluggers. Since MLB added the second wild card in 2012, only 35 of the 71 teams in the top 10 in home runs for a given season went on to make the playoffs (there was a tie for 10th place in home runs last seasons, hence 71 teams instead of 70 in our 10-year sample). The eventual World Series champion has only ranked in the top 10 in homers three times in the past seven seasons.

Moreover, a league-wide rise in home runs has led some teams to avoid paying up for what's become a more readily available commodity. Consider this:

- In 2006, the height of the PED era, there were 23 players who hit 35 or more home runs. That list included Alex Rodriguez, Manny Ramirez and Jason Giambi -- two players who would go on to be suspended for PED use, and one who admitted after the fact to using PEDs. Ryan Howard's 58 homers is now tied for the 11th-highest single-season mark of all time; the year he reached that total, he trailed only Babe Ruth and Roger Maris, as well as Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, two players long rumored to have juiced.

- That 2006 season was also the year that Major League Baseball enacted its Joint Drug Prevention and Treatment Program, aimed at snuffing out and punishing PED users after decades of looking the other way.

- Just four years later, only six players hit 35 home runs. Four years later after that (2014), only seven players reached the 35-homer mark.

- In each of the four seasons since (2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018), at least 15 players have launched 35 bombs, with an average of 16.5 players per season smashing that many.

In the midst of that growing supply, front offices have also become more analytically savvy than ever before. They recognize that there are lots of ways to score runs that don't involve the long ball. Perusing the 2018 leaderboards, we find 27 players who hit 30 or more home runs last season, and also 27 batting title-qualified hitters who fared 30 percent better than league average (or more) by the park-adjusted stat wRC+.

Comparing the top 27 of each list, exactly one-third of the players on the wRC+ leaderboard did not appear on the home run leaderboard, meaning they didn't need massive homer totals to be top-shelf hitters. That list includes perennially elite players like Joey Votto, Jose Altuve, Freddie Freeman and Anthony Rendon, and also surprise names like Mitch Haniger, Matt Chapman, Xander Bogaerts and criminally underrated Mets outfielder Brandon Nimmo.

Here, we're only talking offense. Teams increasingly recognize that position players can deliver enormous value with their defense and their legs too -- and now they're finally starting to compensate players that way, instead of overpaying for Triple Crown stats the way they did in the past. Twelve of the 30 leaders on 2018's leaderboard for the all-encompassing stat Wins Above Replacement hit fewer than 25 home runs.

In fact the 12th-most valuable position player in the majors last season was Lorenzo Cain, the lightning-fast, Gold Glove-caliber center fielder who hit just 10 homers. Last winter, the Brewers saw the value in Cain's modest-power game, signing the then 31-year-old veteran to a five-year, $80 million contract, the second-biggest free-agent deal given to a position player last winter.

Cain's huge deal at least partially rebuts the notion that teams are refusing to pay real money to older players. While it's true that every GM knows that position players are on average peaking in their mid-20s (and players don't typically become free agents until their late-20s, or older), we've seen plenty of 20-something players (and 30-something players) accept jarringly low salaries lately. The trait those players have in common: They hit for tons of power, and often don't do much else.

We compiled a list of all players who hit 20 or more home runs in the past three seasons, who then went on to sign as a free agent in the offseason that followed. The current offseason, of course, is incomplete. A.J. Pollock, Jed Lowrie and Brian Dozier are still looking for work. Then there's the superstar duo of Manny Machado and Bryce Harper, two free agents with big-time power, but also multiple skills elsewhere, as well as the mid-20s profile so rare in free agents that could drive their next contracts near or over record-setting territory.

Here's that list:

2016

- Mark Trumbo: 3-year, $37.5M deal

- Edwin Encarnacion: 3-year, $60M deal

- Chris Carter: 1-year, $3.5M deal

- Mike Napoli: 1-year, $8.5M deal

- Yoenis Cespedes: 4-year, $110M deal

- Kendrys Morales: 3-year, $33M deal

- Carlos Beltran: 1-year, $16M deal

- Brandon Moss: 2-year, $12M deal

- Justin Turner: 4-year, $64M deal

- Ryan Howard: Minor-league deal

- Michael Saunders: 1-year, $9M deal

- Pedro Alvarez: Minor-league deal

- Jose Bautista: 1-year, $18M deal

- Ian Desmond: 5-year, $70M deal

- Mitch Moreland: 1-year, $5.5M deal

- Wilson Ramos: 2-year, $12.5M deal

- Matt Holliday: 1-year, $14M deal

- Adam Lind: 1-year, $1M deal

2017

- Todd Frazier: 2-year, $17M deal

- Carlos Santana: 3-year, $60M deal

- Jay Bruce: 3-year, $39M deal

- Curtis Granderson: 1-year, $5M deal

- Eric Hosmer: 8/$144M deal

- Jose Bautista: 1-year, $1M deal

- J.D. Martinez: 5/$110M deal

- Mitch Moreland: 2-year, $13M deal

- Logan Morrison: 1-year, $6.5M deal

- Mike Moustakas: 1-year, $6.5M deal

- Lucas Duda: 1-year, $3.5M deal

- Mark Reynolds: Minor-league deal

- Mike Napoli: Minor-league deal

- Yonder Alonso: 2-year, $16M deal

- Zack Cozart: 3-year, $38M deal

- Matt Adams: 1-year, $4M deal

- Welington Castillo: 2-year, $15M deal

2018

- Ian Kinsler: 2-year, $8M deal

- Andrew McCutchen: 3-year, $50M deal

- Justin Bour: 1-year, $2.5M deal

- Matt Adams: 1-year, $4M deal

- Nelson Cruz: 1-year, $14.3M deal

- Jonathan Schoop: 1-year, $7.5M deal

Clearly, hitting 20 home runs isn't as exciting as it used to be. Some takeaways here:

Name value doesn't count for much anymore. The former MVP Howard had to settle for a minor-league deal after his 25-homer performance in 2016. Six-time All-Star Jose Bautista managed a measly one-year, $1 million deal after swatting 23 big flies in 2017. Granted, Howard also hit .196 that same year and had been declining for a long time by the time he hit the open market.

Bautista's case is the one that really hits home. On the eve of the 2016 season, Bautista said he would need a five-year, $150 million deal to convince him to stay with the Blue Jays. At that point, we were talking about a player who'd made six straight All-Star Games, bashing 227 homers over those six seasons, with gaudy on-base percentages to boot. During any part of the free-agency era, Bautista could've expected a windfall for those numbers. That includes the PED era, when teams often bet on players well into their 30s sustaining their performance for several more seasons, and often had those bets pay off.

Not this time. Bautista was 35 years old when he made that $150 million proclamation. And while he'd become a superstar and the bat-flipping face of an ascendant Jays franchise, Father Time was working against him. Jays management never came close to offering that kind of money, and Bautista's performance (both with the bat and glove) tanked over the next two years. When he did finally hit free agency, potential suitors didn't see all those home runs and clutch performances from his past. They saw a 37-year-old player who'd just hit .203 with a .308 on-base percentage, with plummeting speed and defensive utility. He got paid accordingly.

Howard was one of four players in our sample who could do no better than a minor-league deal. That includes Mark Reynolds, the Rockies first baseman who not only hit 30 homers and drove in 97 runs in 2017, but also batted a solid .267/.352/.487 that year, a mark four percent better than league average even after adjusting for the friendly confines of Coors Field. Not only did he get nothing more than a minor-league deal from Washington for his efforts -- he didn't even sign with the Nationals until April 17 of the following season.

Reynolds, like Howard and Bautista, was well into his 30s when the market ignored him. But age is from the only factor driving teams' disdain for power.

Consider Corey Dickerson. In 2015, his first full major-league season, Dickerson batted a terrific .312/.364/.567 with 24 home runs, cementing himself as one of the best young hitters in the league, Coors Field be damned. He slipped to .304/.333/.536 the next season, but those diminished numbers and his modest 65 games played total could be pegged to plantar fasciitis and rib injuries. This was still a 26-year-old outfielder who'd shown he could hit for average and power, with four years of controllable service time to boot. The Rockies traded him anyway, sending him to Tampa Bay for veteran reliever Jake McGee and pitching prospect German Marquez.

In hindsight, that deal has proven to be a grand slam for the Rockies, far more for Marquez unexpectedly developing into a top-flight pitcher than for the two years of control they got with McGee. More puzzling was the trade that happened two years later, when the Rays flipped the then-28-year-old Dickerson to Pittsburgh for unspectacular reliever Daniel Hudson and B-level prospect Tristan Gray. This after Dickerson blasted 27 more homers for the 2017 Rays (with park-adjusted numbers 18 percent better than league average).

For a more recent example, there's C.J. Cron. The Angels made Cron their first-round pick (17th overall) in the 2011 draft, hoping to land a future middle-of-the-lineup power hitter. That power was slow to materialize, though, with Cron never hitting more than 16 home runs nor slugging better than .467 in his four seasons with the Halos. With Cron up for arbitration amid that middling track record, the Angels traded him to the Rays in February for nothing more than a player to be named later.

Then, he mashed. Cron walloped 30 home runs last season for Tampa Bay, his .253/.323/.493 batting line grading out to 22 percent better than league average after adjusting for pitcher-friendly Tropicana Field -- making him the 22nd-best qualified hitter in the American League. But with Cron up for arbitration again, the Rays didn't even bother tendering him a contract offer, instead setting him free. Cron's defense has ranged from a bit better than average with the Angels to a tick below with the Rays (per Baseball Info Solutions' Defensive Runs Saved). He runs about as well as you'd expect for a 6-foot-4, 235-pound first baseman/DH, which is to say, not that well.

Still, seeing the Rays not even try to retain Cron was a surprise. A few years ago, we might have seen a minor bidding war for a 28-year-old first baseman coming off a 30-homer season. This time, the Twins needed only a one-year, $4.8 million contract offer -- just a few hundred thousand dollars more than MLB's average salary (itself heavily weighed down by the hundreds of pre-arbitration players toiling in the majors) -- to reel him in.

With the bargain-basement signings of Cron, Cruz and the 67 combined home runs they hit last season, there just might be something brewing in Minnesota.

We mentioned that Cruz leads the majors in home runs over the past five seasons. He also leads the majors in homers for the past 10 seasons, and he's the only player to hit 35 or more bombs in each of the past five. Unlike Cron, Cruz (himself a once-busted PED user) is ancient by post-PED era standards. But his underlying skills still look strong.

In a season in which he turned 38 years old, Cruz ranked second in the majors in exit velocity. He ranked seventh in percentage of batted balls hit at least 95 mph. He ranked 11th in barrel percentage, which is the frequency with which a hitter connects with balls on the sweet spot of their bat. Add it all up and Cruz was the 10th-best hitter in the AL, batting a strong .256/.342/.509 at offense-suppressing T-Mobile Park.

Many factors took the Twins from 2017 surprise wild-card winners to 2018 sub-.500 afterthoughts. Byron Buxton played in just 28 major-league games due to injuries, a demotion, and a bizarre lack of a September callup. Lance Lynn and Logan Morrison were free-agent busts. And so on.

But sometimes, baseball isn't that complicated. The Twins ranked just 23rd in the majors in home runs last season; AL Central-winning Cleveland ranked sixth. So Minnesota and went out and addressed one of their biggest weaknesses, and did so for nothing more than a pair of one-year contracts. With Corey Kluber on the trade block (thus potentially closing the big starting pitching gap that also played a big role in Cleveland running away with the division last season), Buxton and Miguel Sano carrying serious bounce-back potential, and several other young players offering upside, you could start to daydream on the Twins possibly dethroning the three-time defending champs in Cleveland. Landing two sluggers that cheaply improves those odds.

The broader question is if the Twins might have stumbled on a new market inefficiency in baseball. Just a few years ago, following the PED era and the concurrent drop in home runs, every exec worth his salt went begging for power, particularly right-handed power. Now that home runs have spiked back up and models like WAR tell us that power and wins don't always go together, teams have gone from careful skepticism when it comes to big-dollar contracts for sluggers, all the way to tossing them to the curb with Tuesday morning's trash.

But power still plays. The top two homer-hitting teams in 2018 were the Yankees and A's, both of whom stormed to the playoffs. The top two home-run hitters in the majors were Khris Davis and J.D. Martinez. Davis helped lead an A's team nobody expected to do all that well to a 97-win season. All Martinez did was install a fearsome threat in the middle of Boston's lineup that helped propel the Sox to a World Series title. Martinez did get paid for his talents, though less than the six-year deal he sought, and about half of what a comparable free agent, Prince Fielder, got a few years earlier. Meanwhile Davis has been forced to settle for year-to-year arbitration negotiations; if the A's put him up for trade, it's unlikely he'd fetch a ton in return.

Maybe, just maybe, teams should take a second look at what's happening. Offense is down league-wide, with declines in batting average, OBP, slugging, and runs scored. Defensive shifts have been blamed for that decline, though that explanation likely doesn't hold water, all things considered; improved pitching and smarter usage of pitching staffs by managers likely play a much bigger role.

What we do know is that you can't shift your second baseman or shortstop into the bleachers. At a time when everyone and their mom is throwing 99 out of the pen, hits are harder to come by, and so too are runs, wouldn't investing in the easiest way to score a run make some sense? At the very least, wouldn't a one-year deal for the most prolific slugger in the game, or picking up a 28-year-old, 30-homer guy for less than Jordy Mercer's 2019 salary be worth a shot?

In the copycat world that is Major League Baseball, keep an eye on the Twins. If they storm back to the playoffs on a raft of Cruz and Cron walkoffs, maybe all those miserly contracts for sluggers can finally rebound. Maybe power hitters can rise up, and return from the dead.